|

By Alan Joch

Moving into the new century

What does an electronics company do when its showpiece technology

lab starts to show its age? For Sony Corporation, the answer

was to renovate, to the tune of $4 million and months of brainstorming.

Sony’s four-story Wonder Technology Lab, designed by

Ed Schlossberg, opened in New York City in 1994—an epoch

ago measured in high-tech time. “We wanted to move from

analog facility to digital facility,” says Ann Morfogen,

a Sony senior vice president. Sony also wanted to differentiate

the renovation from a design perspective. “When the lab

first opened, people were wowed by the physical language of

technology—the wires, connections, and hardware,”

notes the project’s architect, Lee H. Skolnick, FAIA,

principal of Lee H. Skolnick Architecture + Design Partnership

in New York. “It was a case of wearing technology on

your sleeve.”

In the renovation, which opened in October, the emphasis

is instead on integrating technology into the physical design.

“We wanted a look that was modern, cool, comfortable—and

to forget about the hardware,” Skolnick says. A team

from Sony joined forces with Skolnick’s group and an

A/V systems integrator for six months of “creative interaction,”

Morfogen says. Josh Weisberg, principal of the systems integrator,

Scharff Weisberg of Queens, joined the team early because

the underlying A/V needs would be key to bringing the creative

ideas to life. “We couldn’t simply use consumer

devices—we had to take the technology to the next level

with sophisticated computer systems to handle all of this

processing,” Skolnick says. The majority of the computers

run in a behind-the-scenes, 8-by-12-foot room where custom-designed

controls automatically run digital-video servers and the lighting

system.

|

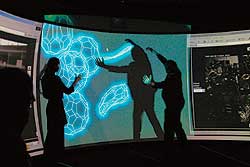

Visitors to LACMA’s

nano play with supersize images of molecules called

Buckyballs, named for their resemblance to Buckminster

Fuller’s domes.

Photography:Courtesy UCLA Academic Technology Services

staff |

|

|

Because it wanted to emphasize the “magic” of technology,

the design group eschewed monitors and keyboards in favor

of wall-size video projections, vibrating floors, and sensor-activated

instruments that place visitors within the exhibits, Weisberg

says.

For example, the games exhibit isn’t merely an arcade

to display the latest and greatest video systems—instead,

visitors find themselves immersed in a game thanks to A/V

technology such as directional sound and large-screen monitors.

A related exhibit lets visitors create a racetrack and cars

for their own auto racing game. This “activated environment,”

Skolnick says, relies on modulated lighting and video images

that move across the floors. A curved wall stretches throughout

the renovated second-floor space to act as a common design

element, tying the exhibits together. Made of a custom lenticular

material, the wall’s surface ridges are molded at various

angles that refract the changing color patterns shining through

from behind the wall. “As you move through the lab, the

visuals on the wall change,” Skolnick explains. “We

developed a color palette for the entire space, and you see

all of those colors on the wall.” Skolnick worked with

a British supplier to produce the material in large, wall-size

sheets, rather than the small panels typically manufactured

for toys and advertising trinkets. “Using the material

on this scale, as an environmental element, was a new thing,”

Skolnick says.

Another challenge was how to use the open, skylit atrium

space adjacent to the lab to attract attention. “We wanted

people in the atrium to see how visitors in the lab were empowered

to do exciting things,” says Skolnick. The design team

created a video montage, using real-time, live-action scenes

from inside the lab, and a bay window in the atrium as a large

projection screen. To cut down on glare and reflections, they

treated the window with a self-adhesive, high-gain acrylic

film that provides a surface opaque enough to display the

images, but translucent enough to let light pass through.

For Skolnick, whose company has been designing interactive

exhibits for 20 years, the lesson of this project is that

design and technology will continue to become ever more intertwined.

“It’s not about people just pushing buttons, but

rather, it’s creating more natural interfaces to bridge

architecture and technology and make them one.”

|